This continues the interview with Dr. Noel Fallows begun in Part One.

Dr. Noel Fallows is the Associate Dean of International and Multidisciplinary Programs in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences within the University of Georgia. He is also a Fellow of The Society of Antiquaries of London. He has written and co-written several books, including:

The Book of the Order of Chivalry

The Twelve of England

The Chivalric Vision of Alfonso De Cartagena: Study and Edition of the Doctrinal De Los Caualleros

Satire and Invective in Enlightened Spain: Crotalogia, O Ciencia De Las Castanuelas

as well as other books and articles dealing with various aspects of Spanish history.

This interview, which began in Part One, focuses on his award winning book:

Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia.

The interview continues:

Regarding the Rules of jousting

At a tournament in Valladolid, held to commemorate the birth of Charles V's son and heir, you mention how renowned cavalry officer and patron of militaristic treatises Don Beltran de la Cueva(1478?-1559) “In keeping with the festivities, he adopted the persona of 'The Knight of the Serpent' for the duration of the tournament.” (p. 44 – 45). Later, you describe a “fantastic tournament... inspired by the chivalry novel Amadis de Gaula, and called The Adventure of the Enchanted Sword.” (p. 48) How often did knights adopt a persona during a tournament instead of competing under their own name?

This depended on whether or not the tournament had a festive theme of some sort. In the Passo honroso, for example, where the jousts are solemn jousts of war, the competitors all use their regular names, but they come to the enclosure with their visors down so as they can supposedly joust anonymously. At the end of each competition each man raises his visor so as they can recognize each other – a rhetorical conceit known as an anagnorisis, or sudden moment of recognition – and then the winner invites the loser to dinner.

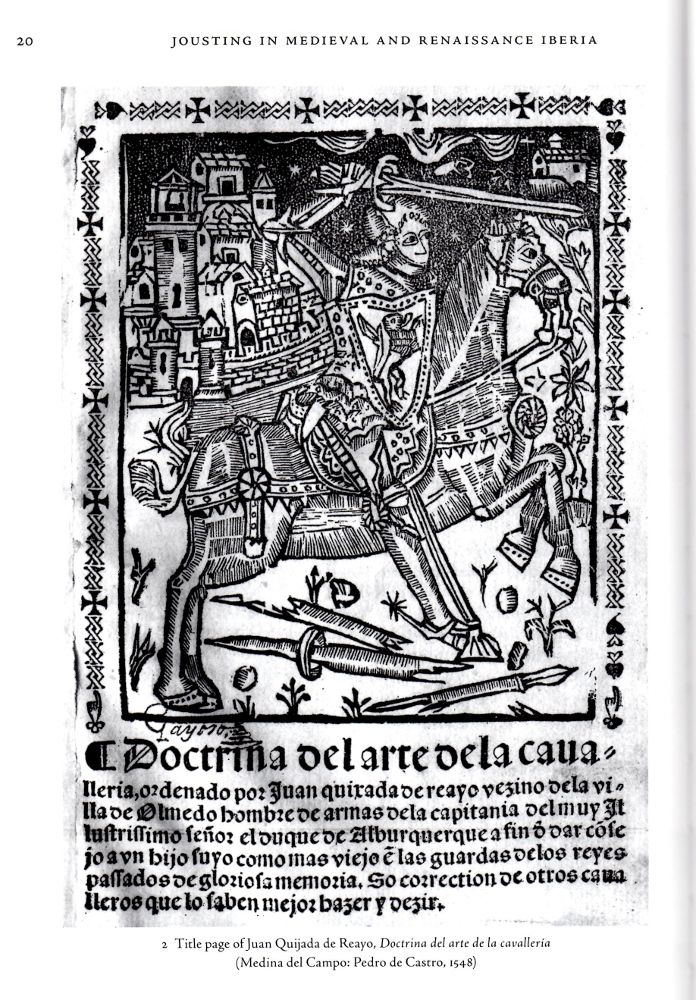

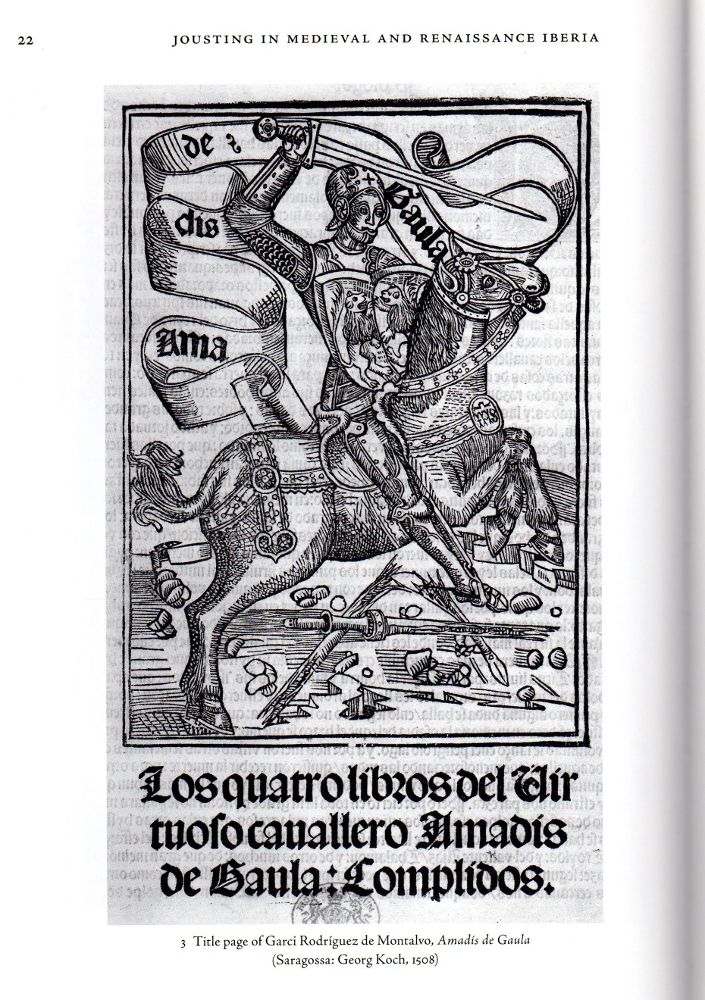

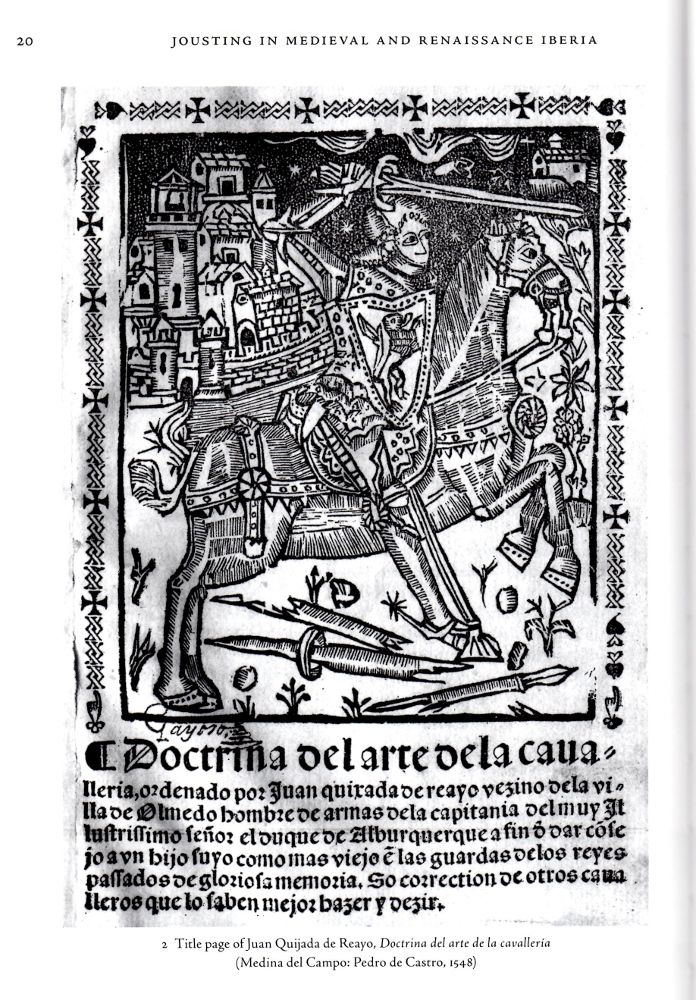

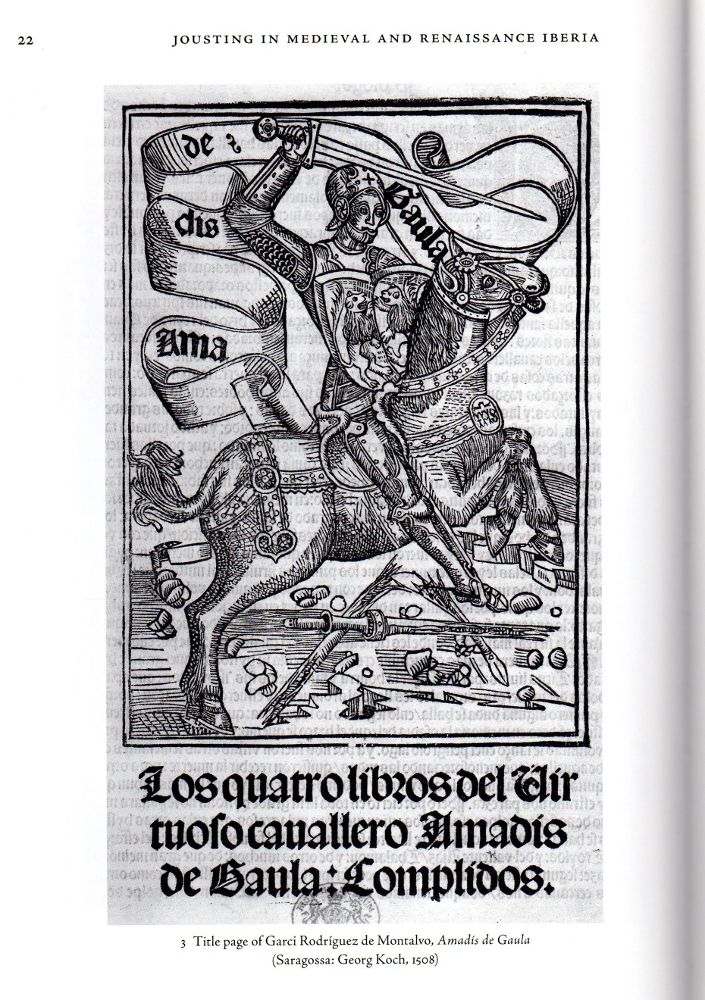

The Spanish jouster Don Luis Zapata says immodestly that he always had trouble jousting anonymously because everyone knew it was him by the distinctive and flashy way that he placed the lance in the lance-rest! He got this idea from his favourite chivalry novel, Amadís of Gaul, as Amadís had the same “problem”. It’s fascinating how back then there was such an interface between the competitions and the popular fiction of the time. As I show in my book, even the presentation of the printed technical manuals emulates the design of the contemporary chivalry novels, a clever sales pitch designed to attract readers and buyers.

Left: The title page of Juan Quijada de Reayo's instructional text Doctrina del arte de la cavalleria

Right: The title page of Garci Rodriquez de Montalvo's fictional text Amadis de Gaula

(images scanned from JMRI, p. 20 & 22)

Was it expected that at certain types of tournaments, everyone would participate in this form of persona play, and that at other tournaments, everyone would compete as themselves? Or did some knights adopt personas and other knights compete as themselves at the same tournaments?

My sense is that you were expected to participate fully in the ethos of the tournament, and that it would therefore be inappropriate to use your own name in a tournament where you were expected to adopt another persona. This, I believe, would make you seem like a spoilsport.

In the tournaments that involved persona play, was the competition any less 'real' than at the tournaments where knights competed under their own names?

I have thought about this a lot! For the Adventure of the Enchanted Sword, the tournament mirrors the novel to such an extent that it almost seems that everyone knew from the start how it was supposed to play out, in which case they were more like actors in a play, but perhaps this was the intention, with some wiggle room for slight differences. In this case the tournament would not have been too different from a modern-day battle reenactment.

In the chapter, “Keeping the Score”, you discuss a number of different historical scoring systems which do not always agree with each other. Sometimes the variance is fairly minor, but other times the different rules seem to directly contradict one another. How do you think this lack of standardization affected the knights, judges and others involved in these various styles of tournaments?

At this time they were attempting to codify the rules so it’s only natural that there were discrepancies. These would have varied from place to place. Even so, the actual lance technique would not have varied so it would just have been a question of checking the rules before starting, and then remembering to abide by them.

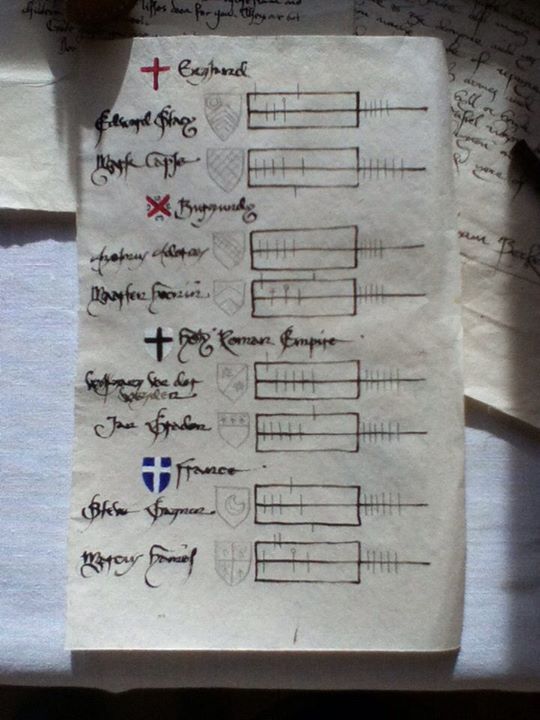

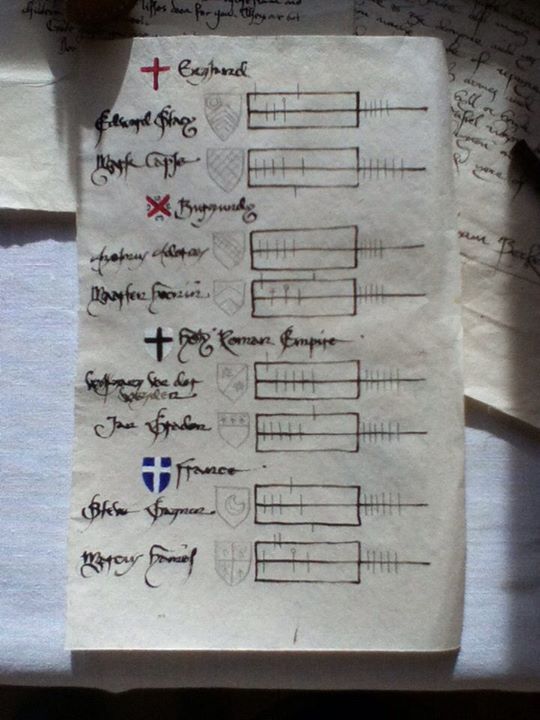

Left: Catherine Tranter carefully scribes the scores for each match at the Arundel International Jousting Tournament 2013(photo by Stephen Moss)

Right: The scoring sheet scribed by Catherine Tranter(photo by Catherine Tranter)

You mention that in regards to jousts, Luis Zapata de Chaves preferred team events over one-on-one competitions. What were the differences between team events and individual competitions?

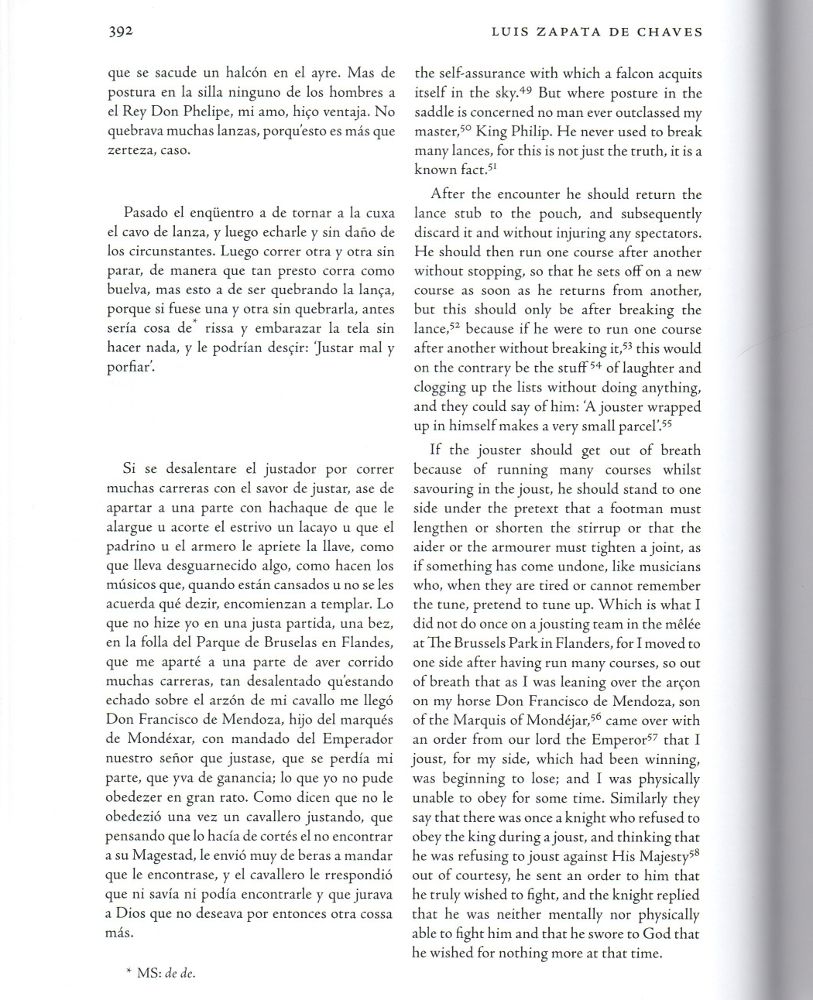

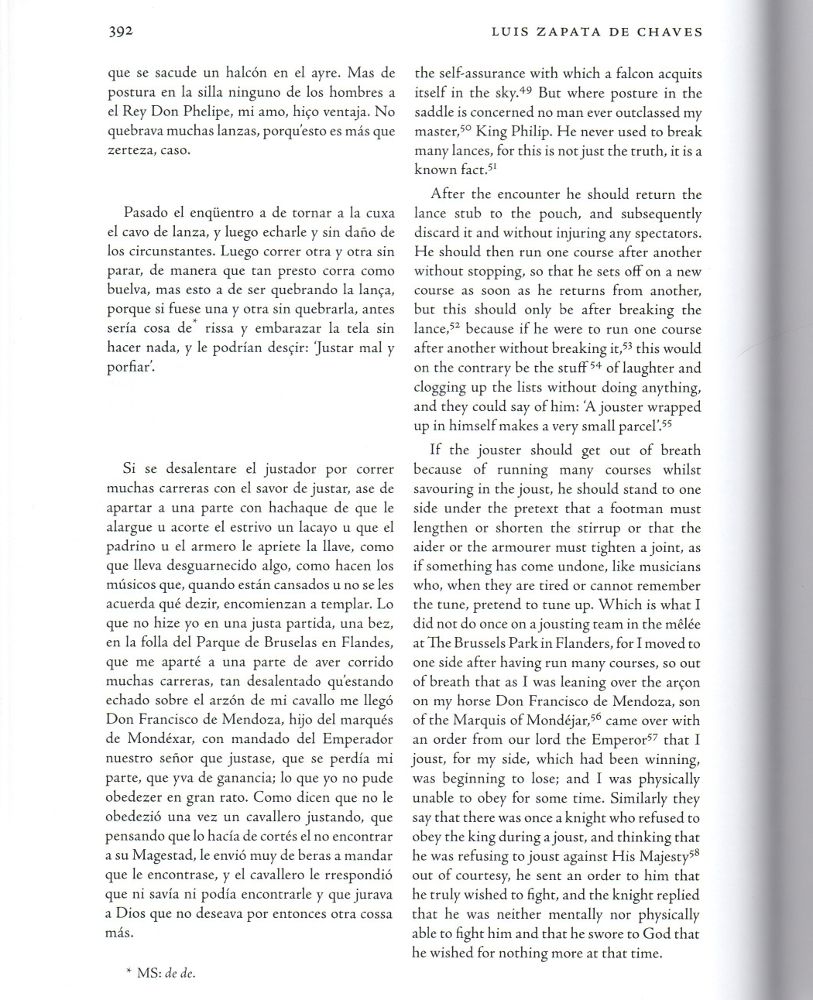

They all still fought one-on-one, but as part of a cohesive team. The evidence suggests that members of each team would have been from the same court, or perhaps the same social class, though if you jousted against the King, he had to win no matter what. See also Zapata’s treatise, p. 393, where he says that the team events move at a much brisker pace and you get to see more lances shatter.

Which kind of tournament, team or individual, do you think occurred more frequently?

Probably both happened equally as frequently.

According to Menaguerra's rules as listed in the chapter “Keeping the Score”: “When royals joust against non-royals, the rules are irrelevant, for the royals always win.” (p. 223) Considering the risks – both political and physical – why do think that non-royals would ever joust against royals?

Generally they didn’t! See Zapata’s treatise p. 392 where the Emperor Charles V is basically pleading with people to joust with him and eventually just orders them to joust with him.

Page 392, showing the original language on the left and Dr. Fallows translation on the right

(scan from JMRI)

On page 248, you describe how attempts to standardize the size of the estoc(a type of sword carried by knights to be used after the lance was discarded) took place during at least four Cortes(legislative meetings) between 1542 and and 1558, and that even after laws were passed creating standardized lengths for estocs, not all blades conformed to these standards(though most apparently did). Considering the difficulties that the Spanish government faced in attempting to standardize one piece of knightly equipment, what do you think it would take to standardize the equipment and rules for contemporary competitive jousting?

Despite the official legislation in the Cortes, these estoc laws were obviously very difficult to implement in practice, or even to make sure that everyone knew about the laws. It would probably be easier now in the sense that communication about such matters is much easier, but you will still have to contend with individual preference for one piece of equipment over another, or one design over another. Also I assume that for modern jousters the armour is still very expensive and you couldn’t possibly own multiple armours based on multiple designs. So there is always going to be incompatibility unless you can all agree on wearing one specific kind of armour from a specific period.

Do you think standardization would be a good idea? Why or why not?

Probably not. Isn’t it more fun to replicate multiple different armours from different periods? It might get boring if everyone absolutely had to wear an Avant armour.

In researching all of these different sets of rules and scoring for jousting tournaments, did you ever theorize an ideal standardized set of rules and scoring for jousting tournaments? If so, what would they be?

To tell the truth, no. In the Introduction, last paragraph, I argue for embracing the tensions, paradoxes and contradictions, which is what makes the concept of Chivalry so fascinating.

Regarding Armour

Even in the same historical time period, a variety of styles of armour could be worn based on regional variation and personal preference. Yet, as part of the 'principle of equality' the armour of competing knights had to be determined to be equal by a set of judges, the king-of-arms and the herald. How well do you believe this 'equality of armour' actually worked in practice?

They must have had to look for basic similarities and consistencies in the context of the time. In the Passo honroso, for example, you were allowed one reinforcing piece, but a specific piece is not specified. That said, if one knight chose to reinforce his pauldron, it is assumed that this is the piece that his opponent would reinforce as well. The lances were also carefully weighed and measured. There were 3 types in the Passo honroso: light; medium; heavy. So he who chose a light lance would have jousted against an opponent with a light-weight lance, etc. I think that this is how they managed this issue.

Which style(s) of armour do you personally prefer in terms of functionality for the joust? In terms of aesthetics? Or for any other reason? And why?

I must say that for all three of the above I really like the fluid yet sturdy look of the mid sixteenth-c. armours, with some conservative etching that adds to the design and style but without being gaudy.

The jousting armour of King Phillip II of Spain is one of Noel's favorite armours. It was made by Wolfgang Grosschedel of Lanshut, c. 1560. The armour currently resides in the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History in Brussels, Belgium(photo copyright Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History)

Regarding Terminology

In your introduction, you discuss why there is such a lack of academic research into European jousting. You mention two scholars (Anglo and Riquer) that complain about the difficulty of understanding the extant texts on the subject, mainly because of the “lack of unified technical vocabularies and the often circumstantial or elliptic descriptions”(p. 9-10) used to discuss jousting. A lack of a standardized vocabulary with which to discuss jousting is still a problem today. How important do you think it is to the sport of jousting to establish a standardized vocabulary?

A standardized vocabulary would probably be beneficial so as to avoid confusion. In the case of the early treatises that I have studied, one reviewer of my book notes that even if you are a native-speaker of Spanish or Catalan you won’t be able to understand these texts without my translation into modern English, such is their impenetrability.

These days we have the luxury of the Internet for instant dissemination of new terminology. In particular in the field of technology, terms that have a standard meaning are adapted to new meanings, e.g. there is adobe (the building material) and there is an acrobat (a type of performer), and then there is Adobe Acrobat. One click on the Internet explains the new meaning.

In the Middle Ages the jousters used the medieval equivalent of the Internet, the printing press, to try to get the word out. The problem is that they often failed to include a definition of the term. A fine example is Ponç de Menaguerra’s treatise which refers to a piece of armour called the “caracol”. The standard definition of this word is “snail”, but that is clearly not the new technological meaning. It took me years to figure out that he was referring to the flaon bolt that holds the shield in place.

The flaon bolt is clearly visible on the left(his left) side of Toby Capwell's jousting armour. You can also see the arret(lance rest) on the other side(photo by Ben van Koert/Kaos Historicalal Media)

Here you can see just the nut that goes with the flaon bolt as it holds Dominic Sewell's ecranche(jousting shield) in place(photo by Ulrike Otto)

Since you prefer to avoid the historically inaccurate phrase 'suit of armour', which of the three more accurate terms that you suggest using instead – 'armour', 'harness' and 'garniture' – is actually your preferred term? And why do you prefer it?

I think in the book I use “armour” the most. It’s an easy and sensible term for what is being described. To me, “garniture” has a more specific meaning of a host armour accompanied by other pieces that can be worn over it. “Harness” is a less familiar term to the general reader.

Are there other words or phrases related to jousting that you see frequently misused that you would like to correct? What are they?

Not that I can think of off-hand. I was dismayed to see in a recent scholarly book about Chivalry which shall remain nameless that the author perpetuates the ridiculous idea that armour was so heavy that knights were hoisted onto their horses by cranes. I just don’t know why this myth persists.

How to Mount a Horse in Armour(video by the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This interview began in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part One"

And will be continued in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part Three"

Related articles:

Video: Dr. Noel Fallows Talks About Chivalry and Jousting

Arundel Castle International Jousting Tournament 2013

There are also numerous articles about The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel

Dr. Noel Fallows is the Associate Dean of International and Multidisciplinary Programs in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences within the University of Georgia. He is also a Fellow of The Society of Antiquaries of London. He has written and co-written several books, including:

The Book of the Order of Chivalry

The Twelve of England

The Chivalric Vision of Alfonso De Cartagena: Study and Edition of the Doctrinal De Los Caualleros

Satire and Invective in Enlightened Spain: Crotalogia, O Ciencia De Las Castanuelas

as well as other books and articles dealing with various aspects of Spanish history.

This interview, which began in Part One, focuses on his award winning book:

Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia.

The interview continues:

Regarding the Rules of jousting

At a tournament in Valladolid, held to commemorate the birth of Charles V's son and heir, you mention how renowned cavalry officer and patron of militaristic treatises Don Beltran de la Cueva(1478?-1559) “In keeping with the festivities, he adopted the persona of 'The Knight of the Serpent' for the duration of the tournament.” (p. 44 – 45). Later, you describe a “fantastic tournament... inspired by the chivalry novel Amadis de Gaula, and called The Adventure of the Enchanted Sword.” (p. 48) How often did knights adopt a persona during a tournament instead of competing under their own name?

This depended on whether or not the tournament had a festive theme of some sort. In the Passo honroso, for example, where the jousts are solemn jousts of war, the competitors all use their regular names, but they come to the enclosure with their visors down so as they can supposedly joust anonymously. At the end of each competition each man raises his visor so as they can recognize each other – a rhetorical conceit known as an anagnorisis, or sudden moment of recognition – and then the winner invites the loser to dinner.

The Spanish jouster Don Luis Zapata says immodestly that he always had trouble jousting anonymously because everyone knew it was him by the distinctive and flashy way that he placed the lance in the lance-rest! He got this idea from his favourite chivalry novel, Amadís of Gaul, as Amadís had the same “problem”. It’s fascinating how back then there was such an interface between the competitions and the popular fiction of the time. As I show in my book, even the presentation of the printed technical manuals emulates the design of the contemporary chivalry novels, a clever sales pitch designed to attract readers and buyers.

Left: The title page of Juan Quijada de Reayo's instructional text Doctrina del arte de la cavalleria

Right: The title page of Garci Rodriquez de Montalvo's fictional text Amadis de Gaula

(images scanned from JMRI, p. 20 & 22)

Was it expected that at certain types of tournaments, everyone would participate in this form of persona play, and that at other tournaments, everyone would compete as themselves? Or did some knights adopt personas and other knights compete as themselves at the same tournaments?

My sense is that you were expected to participate fully in the ethos of the tournament, and that it would therefore be inappropriate to use your own name in a tournament where you were expected to adopt another persona. This, I believe, would make you seem like a spoilsport.

In the tournaments that involved persona play, was the competition any less 'real' than at the tournaments where knights competed under their own names?

I have thought about this a lot! For the Adventure of the Enchanted Sword, the tournament mirrors the novel to such an extent that it almost seems that everyone knew from the start how it was supposed to play out, in which case they were more like actors in a play, but perhaps this was the intention, with some wiggle room for slight differences. In this case the tournament would not have been too different from a modern-day battle reenactment.

In the chapter, “Keeping the Score”, you discuss a number of different historical scoring systems which do not always agree with each other. Sometimes the variance is fairly minor, but other times the different rules seem to directly contradict one another. How do you think this lack of standardization affected the knights, judges and others involved in these various styles of tournaments?

At this time they were attempting to codify the rules so it’s only natural that there were discrepancies. These would have varied from place to place. Even so, the actual lance technique would not have varied so it would just have been a question of checking the rules before starting, and then remembering to abide by them.

Left: Catherine Tranter carefully scribes the scores for each match at the Arundel International Jousting Tournament 2013(photo by Stephen Moss)

Right: The scoring sheet scribed by Catherine Tranter(photo by Catherine Tranter)

You mention that in regards to jousts, Luis Zapata de Chaves preferred team events over one-on-one competitions. What were the differences between team events and individual competitions?

They all still fought one-on-one, but as part of a cohesive team. The evidence suggests that members of each team would have been from the same court, or perhaps the same social class, though if you jousted against the King, he had to win no matter what. See also Zapata’s treatise, p. 393, where he says that the team events move at a much brisker pace and you get to see more lances shatter.

Which kind of tournament, team or individual, do you think occurred more frequently?

Probably both happened equally as frequently.

According to Menaguerra's rules as listed in the chapter “Keeping the Score”: “When royals joust against non-royals, the rules are irrelevant, for the royals always win.” (p. 223) Considering the risks – both political and physical – why do think that non-royals would ever joust against royals?

Generally they didn’t! See Zapata’s treatise p. 392 where the Emperor Charles V is basically pleading with people to joust with him and eventually just orders them to joust with him.

Page 392, showing the original language on the left and Dr. Fallows translation on the right

(scan from JMRI)

On page 248, you describe how attempts to standardize the size of the estoc(a type of sword carried by knights to be used after the lance was discarded) took place during at least four Cortes(legislative meetings) between 1542 and and 1558, and that even after laws were passed creating standardized lengths for estocs, not all blades conformed to these standards(though most apparently did). Considering the difficulties that the Spanish government faced in attempting to standardize one piece of knightly equipment, what do you think it would take to standardize the equipment and rules for contemporary competitive jousting?

Despite the official legislation in the Cortes, these estoc laws were obviously very difficult to implement in practice, or even to make sure that everyone knew about the laws. It would probably be easier now in the sense that communication about such matters is much easier, but you will still have to contend with individual preference for one piece of equipment over another, or one design over another. Also I assume that for modern jousters the armour is still very expensive and you couldn’t possibly own multiple armours based on multiple designs. So there is always going to be incompatibility unless you can all agree on wearing one specific kind of armour from a specific period.

Do you think standardization would be a good idea? Why or why not?

Probably not. Isn’t it more fun to replicate multiple different armours from different periods? It might get boring if everyone absolutely had to wear an Avant armour.

In researching all of these different sets of rules and scoring for jousting tournaments, did you ever theorize an ideal standardized set of rules and scoring for jousting tournaments? If so, what would they be?

To tell the truth, no. In the Introduction, last paragraph, I argue for embracing the tensions, paradoxes and contradictions, which is what makes the concept of Chivalry so fascinating.

Regarding Armour

Even in the same historical time period, a variety of styles of armour could be worn based on regional variation and personal preference. Yet, as part of the 'principle of equality' the armour of competing knights had to be determined to be equal by a set of judges, the king-of-arms and the herald. How well do you believe this 'equality of armour' actually worked in practice?

They must have had to look for basic similarities and consistencies in the context of the time. In the Passo honroso, for example, you were allowed one reinforcing piece, but a specific piece is not specified. That said, if one knight chose to reinforce his pauldron, it is assumed that this is the piece that his opponent would reinforce as well. The lances were also carefully weighed and measured. There were 3 types in the Passo honroso: light; medium; heavy. So he who chose a light lance would have jousted against an opponent with a light-weight lance, etc. I think that this is how they managed this issue.

Which style(s) of armour do you personally prefer in terms of functionality for the joust? In terms of aesthetics? Or for any other reason? And why?

I must say that for all three of the above I really like the fluid yet sturdy look of the mid sixteenth-c. armours, with some conservative etching that adds to the design and style but without being gaudy.

The jousting armour of King Phillip II of Spain is one of Noel's favorite armours. It was made by Wolfgang Grosschedel of Lanshut, c. 1560. The armour currently resides in the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History in Brussels, Belgium(photo copyright Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History)

Regarding Terminology

In your introduction, you discuss why there is such a lack of academic research into European jousting. You mention two scholars (Anglo and Riquer) that complain about the difficulty of understanding the extant texts on the subject, mainly because of the “lack of unified technical vocabularies and the often circumstantial or elliptic descriptions”(p. 9-10) used to discuss jousting. A lack of a standardized vocabulary with which to discuss jousting is still a problem today. How important do you think it is to the sport of jousting to establish a standardized vocabulary?

A standardized vocabulary would probably be beneficial so as to avoid confusion. In the case of the early treatises that I have studied, one reviewer of my book notes that even if you are a native-speaker of Spanish or Catalan you won’t be able to understand these texts without my translation into modern English, such is their impenetrability.

These days we have the luxury of the Internet for instant dissemination of new terminology. In particular in the field of technology, terms that have a standard meaning are adapted to new meanings, e.g. there is adobe (the building material) and there is an acrobat (a type of performer), and then there is Adobe Acrobat. One click on the Internet explains the new meaning.

In the Middle Ages the jousters used the medieval equivalent of the Internet, the printing press, to try to get the word out. The problem is that they often failed to include a definition of the term. A fine example is Ponç de Menaguerra’s treatise which refers to a piece of armour called the “caracol”. The standard definition of this word is “snail”, but that is clearly not the new technological meaning. It took me years to figure out that he was referring to the flaon bolt that holds the shield in place.

The flaon bolt is clearly visible on the left(his left) side of Toby Capwell's jousting armour. You can also see the arret(lance rest) on the other side(photo by Ben van Koert/Kaos Historicalal Media)

Here you can see just the nut that goes with the flaon bolt as it holds Dominic Sewell's ecranche(jousting shield) in place(photo by Ulrike Otto)

Since you prefer to avoid the historically inaccurate phrase 'suit of armour', which of the three more accurate terms that you suggest using instead – 'armour', 'harness' and 'garniture' – is actually your preferred term? And why do you prefer it?

I think in the book I use “armour” the most. It’s an easy and sensible term for what is being described. To me, “garniture” has a more specific meaning of a host armour accompanied by other pieces that can be worn over it. “Harness” is a less familiar term to the general reader.

Are there other words or phrases related to jousting that you see frequently misused that you would like to correct? What are they?

Not that I can think of off-hand. I was dismayed to see in a recent scholarly book about Chivalry which shall remain nameless that the author perpetuates the ridiculous idea that armour was so heavy that knights were hoisted onto their horses by cranes. I just don’t know why this myth persists.

How to Mount a Horse in Armour(video by the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This interview began in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part One"

And will be continued in:

"An Interview with Dr. Noel Fallows, Author of Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: Part Three"

Related articles:

Video: Dr. Noel Fallows Talks About Chivalry and Jousting

Arundel Castle International Jousting Tournament 2013

There are also numerous articles about The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel

No comments:

Post a Comment